Doing science is exciting, fun, and full of big ideas! Why bother with writing when you could be mixing up chemicals, blasting rockets, or shattering laser beams?

Doing science is exciting, fun, and full of big ideas! Why bother with writing when you could be mixing up chemicals, blasting rockets, or shattering laser beams?Because all your "great ideas" are worth nothing if you can't tell others about what you're doing. Scientists write in journals to let others know the latest news with their experiments, announce their new discoveries, or to simply keep track of their progress.

You don't have to write a novel - just keep track of what you're doing along with any questions that come up. It's a lot easier to do a couple pages a day for a month rather than trying to pound out a hundred pages in a day! This is something you're going to use throughout the program doing just a little bit at a time, At the end of the month or year, you'll be surprised to see how much science you've covered!

There are three simple steps to this process:

Grab, Title, and Record

Step 1:Grab a notebook.

You don't need a fancy quad-ruled, glossy bound, gold-letter-embossed notebook, either. Just find a regular spiral-bound notebook from the store and scribble your child's name across the top. (You can even staple ten blank pages together and call it a notebook if you really want to.)

Step 2: Title the top of a fresh page with the name of the lesson or experiment.

For example, from Unit 1, you'd write: Gravity. Easy so far, right? Add the date and time to the top corner and number your pages (in case you need to reference them later on. Trust me - it's a lot easier to number as you go).Step 3: Record by describing what you're doing.

If you're reading about gravity, jot down a few notes about what you picked up. This is where you want to capture your Ah-HA! moments. If getting your child to write is harder than changing a car transmission in a snowstorm, then grab a video camera and record them as they work and talk their way through the experiment. Just have them describe what they are doing as they do it (you can probe them along with questions if they get stuck for words). For shyer kids, don't have them look at the camera - in fact, if you focus the camera only on their hands as they work through an experiment, their shyness usually will vanish.

If you're reading about gravity, jot down a few notes about what you picked up. This is where you want to capture your Ah-HA! moments. If getting your child to write is harder than changing a car transmission in a snowstorm, then grab a video camera and record them as they work and talk their way through the experiment. Just have them describe what they are doing as they do it (you can probe them along with questions if they get stuck for words). For shyer kids, don't have them look at the camera - in fact, if you focus the camera only on their hands as they work through an experiment, their shyness usually will vanish.A lot of scientists and engineers carry around a voice recorder, so when they have a GREAT IDEA, they can quickly capture it with words by hitting the 'record' button (even while driving!). This allows them to quickly capture and talk about the idea without fussing with the slowness of a pencil and paper. They later play it back and jot down notes and expand it when they have more time.

If you love to write and draw, simply write down the experiment or reading bullet points and illustrate with pictures, describing it with real words that make sense to you. Don't worry about it not being 'formal' or 'correct' - this is your journal, not for anyone else.

For example, if you're launching the potato cannon (which we'll actually be doing later on), and you finally figured out how it worked, we'd rather see you write: "I shoved the stick in, which squashed the air, and POP!"

instead of "...as the lowermost potato slug was moved in an upward direction, the pressure increased as the volume decreased until the structural integrity of the uppermost potato was breached, at which time the..." Use words that really speak to you in your own terms. You are not writing a textbook, but rather capturing the essence of the experience you're having as you learn science. Got it?

Also, if you have any questions that pop up along the way (especially ones that require more time to search for the answers), write them down here as well. Highlight or *star* each question so you remember to go back and get them answered when you have more time.

Also, if you have any questions that pop up along the way (especially ones that require more time to search for the answers), write them down here as well. Highlight or *star* each question so you remember to go back and get them answered when you have more time.If you're recording your progress on a science experiment, get your picture taken as you are doing the experiment and paste it in the notebook. Add a caption about what you are doing, what you found, etc. Most scientists will also record any data they took for the experiment alongside the picture of their set up so it's all in one place.

An excellent idea many families have reported using is at the end of the unit, the parents will become the student and the kids teach the lesson back to the parent until the parent gets it. This may take a bit of work of the kid's part, but most of the time, you'll find kids are determined and creative at getting their point across because they are so excited and passionate about what they have just learned. (Don't believe us? Try faking ignorance and see what your child comes up with.)

And that's it! Do you think this is something you can do?

If so, you've just boosted yourself to the top 10% of the students worldwide that actually take the time to capture and record their work. If you just hear or read something only one time, you will only remember 12% of it after about a week. However, when you capture and record notes about what you're doing, the retention after a week shoots up to over 65%. When you take it one step further and teach it to others, you're now over 85% retention after the first month.Turning your Science Journal into Homework You Can Hand In

Once you've mastered the basic steps to keeping a science journal, you can easily match it with your state's requirements for science, provide it as a writing sample with your college application (especially if it contains photos of you taking data), or show it it to your adviser.

Your experiments aren't going to be useful if you can't tell other people about it. There's a standard format that most scientists follow, and that's what we're going to cover here. When you practice these essential steps, your child will be light-years ahead of the game when they hit college. Your kids will not just know the steps on an intellectual level, but it will become built into their nervous system through habit and be a guide as they work through their homework for years to come.

Writing a Rock-Solid Science Journal Report

Once you've gotten into the habit of Grab, Title, and Record, now it's time to put a little more structure into the 'Record' section. I'm going to share with you how we teach engineering students to keep their lab books at the University. This is the same techniques used by astronomers, automotive designers, nuclear engineers, and NASA scientists.When you use this approach when working through the activities, projects, and experiments in the eScience program, you will have a rock-solid documentation that will pass any curriculum adviser, college-entrance examiner, or state required documentation. And it will be organized, easy to use, and rewarding to flip through years later.

Writing a Rock-Solid Science Journal Report

Step 1: Title

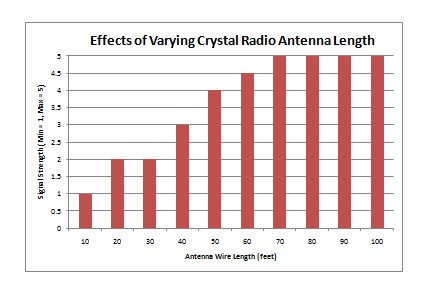

Effects of Antenna Wire Length on Crystal Radio Reception Aurora Lipper November 23, 2010

Step 2: Introduction (Purpose)

Step 3: Materials

- Toilet paper tube

- Magnet wire

- Germanium diode (1N34A)

- Telephone handset or get a crystal earphone

- Alligator clip test leads

- 100’ stranded insulated wire (for the antenna)

- Camera to document project

- Composition or spiral-bound notebook to take notes

- Display board (the three-panel kind with wings), about 48” wide by 36” tall

- Paper for the printer (and photo paper for printing out your photos from the camera)

- Computer and printer

Step 4: Procedure

Step 5: Results

| Crystal Radio Data Sheet | |||

| Name | Aurora Lipper | Antenna wire gauge | 24g |

| Date | Nov. 28, 2009 | Tube wire gauge | 28g magnet |

| Time | 12:45pm | Diode type | germanium |

| Trial # | Antenna Length | Signal Strength | |

| (feet) | (Min = 1, Max =5) | ||

| 1 | 10 | 1 | |

| 2 | 20 | 2 | |

| 3 | 30 | 2 | |

| 4 | 40 | 3 | |

| 5 | 50 | 4 | |

| 6 | 60 | 4.5 | |

| 7 | 70 | 5 | |

| 8 | 80 | 5 | |

| 9 | 90 | 5 | |

| 10 | 100 | 5 | |

|

Step 6: Conclusion

Step 7: References

Whew! So to recap...

Step 1: Title: Effects of Antenna Wire Length on Crystal Radio Reception, by Aurora Lipper, November 23, 2010. This goes at the top of the page.

Step 1: Title: Effects of Antenna Wire Length on Crystal Radio Reception, by Aurora Lipper, November 23, 2010. This goes at the top of the page.

If you're reading about gravity, jot down a few notes about what you picked up. This is where you want to capture your Ah-HA! moments. If getting your child to write is harder than changing a car transmission in a snowstorm, then grab a video camera and record them as they work and talk their way through the experiment. Just have them describe what they are doing as they do it (you can probe them along with questions if they get stuck for words). For shyer kids, don't have them look at the camera - in fact, if you focus the camera only on their hands as they work through an experiment, their shyness usually will vanish.

If you're reading about gravity, jot down a few notes about what you picked up. This is where you want to capture your Ah-HA! moments. If getting your child to write is harder than changing a car transmission in a snowstorm, then grab a video camera and record them as they work and talk their way through the experiment. Just have them describe what they are doing as they do it (you can probe them along with questions if they get stuck for words). For shyer kids, don't have them look at the camera - in fact, if you focus the camera only on their hands as they work through an experiment, their shyness usually will vanish. Also, if you have any questions that pop up along the way (especially ones that require more time to search for the answers), write them down here as well. Highlight or *star* each question so you remember to go back and get them answered when you have more time.

Also, if you have any questions that pop up along the way (especially ones that require more time to search for the answers), write them down here as well. Highlight or *star* each question so you remember to go back and get them answered when you have more time.