How do you find the gravitational potential energy between two objects that are really far apart, like two stars or two galaxies? Here’s how:

Please login or register to read the rest of this content.

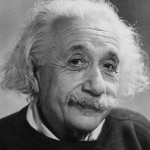

Einstein once said: “I was sitting in a chair in the patent office at Bern when all of the sudden a thought occurred to me: If a person falls freely, he will not feel his own weight. I was startled. This simple thought made a deep impression on me. It impelled me toward a theory of gravitation.”

This led Einstein to develop his general theory of relativity, which interprets gravity not as a force but as the curvature of space and time. This topic is out of the scope for our lesson here, but you can explore more about it in this lesson.

The fundamental principle for relativity is the principle of equivalence, which says that if you were locked up in a box, you wouldn’t tell the difference between being in a gravitational field and accelerating (with an acceleration value equal to g) in a rocket.

The same thing is also true if you were either locked in a box, floating in outer space or in an elevator shaft experiencing free-fall. Any experiments you could do in either of those cases wouldn’t be able to tell you what was really happening outside your box. The way a ball drops is exactly the same in either case, and you would not be able to tell if you were falling in an elevator shaft or drifting in space.

Gravity is the reason behind books being dropped and suitcases feeling heavy. It’s also the reason our atmosphere sticks around and oceans staying put on the surface of the earth. Gravity is what pulls it all together, and we’re going to look deeper into what this one-way attractive force is all about.

One of Newton’s biggest contributions was figuring out how to show that gravity was the same force that caused both objects like an apple to fall to the earth at a rate of 9.81 m/s2 AND the moon being accelerated toward the earth but at a different rate of 0.00272 m/s2. If these are both due to the same force of gravity, why are they different numbers then? Why is the acceleration of the moon 1/3600th the acceleration of objects near the surface of the earth? It has to do with the fact that gravity decreases the further you are from an object. The moon is in orbit about 60 times further from the earth’s center than an object on the surface of the earth, which indicates that gravity is proportional to the inverse of the square of the distance (also called the inverse square law). So the force of gravity acts between any two objects and is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the two centers. The further apart the objects are, the less they force of gravity is between the two of them. If you separate the objects by twice the distance, the gravitational force goes down by a factor of 4.

All objects are attracted to each other with a gravitational force. You need objects the size of planets in order to detect this force, but everything, everywhere has a gravitational field and force associated with it. If you have mass, you have a gravitational attractive force. Newton’s Universal Law of Gravitation is amazing not because he figured out the relationship between mass, distance, and gravitational force (which is pretty incredible in its own right), but the fact that it’s universal, meaning that this applies to every object, everywhere.

Lord Henry Cavendish in 1798 (about a century after Newton) performed experiments with a torsion balance to figure out the value of G. It’s a very small number, so Cavendish had to carefully calibrate his experiment! The reason the number is so small is because we don’t see the effects of gravity until objects are very massive, like a moon or a planet in size.

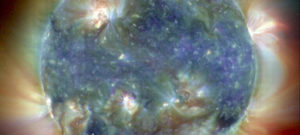

How do astronomers find planets around distant stars? If you look at a star through binoculars or a telescope, you’ll quickly notice how bright the star is, and how difficult it is to see anything other than the star, especially a small planet that doesn’t generate any light of its own! Astronomers look for a shift, or wobble, of the star as it gets gravitationally “yanked” around by the orbiting planets. By measuring this wobble, astronomers can estimate the size and distance of larger orbiting objects.

Doppler spectroscopy is one way astronomers find planets around distant stars. If you recall the lesson where we created our own solar system in a computer simulation, you remember how the star could be influenced by a smaller planet enough to have a tiny orbit of its own. This tiny orbit is what astronomers are trying to detect with this method.

Materials

Weight is nothing more than a measure of how much gravity is pulling on you. This is why you can be “weightless” in space. You are still made of stuff, but there’s no gravity to pull on you so you have no weight. The larger a body is, the more gravitational pull (or in other words the larger a gravitational field) it will have.

The Moon has a fairly small gravitational field (if you weighed 100 pounds on Earth, you’d only be 17 pounds on the Moon). The Earth’s field is fairly large and the Sun has a HUGE gravitational field (if you weighed 100 pounds on Earth, you’d weigh 2,500 pounds on the Sun!).

If you could stand on the Sun without being roasted, how much would you weigh? The gravitational pull is different for different objects. Let’s find out which celestial object you’d crack the pavement on, and which your lightweight toes would have to be careful about jumping on in case you leapt off the planet.

Weight is nothing more than a measure of how much gravity is pulling on you. Mass is a measure of how much stuff you’re made out of. Weight can change depending on the gravitational field you are standing in. Mass can only change if you lose an arm.

Materials

First we’re going to assume the earth is like a ball in that it’s a perfect sphere, and also that the density of the earth is even and it depends only how far from the center of the earth you are. Let’s also assume the earth isn’t rotating. Once we have these things in mind, then the magnitude of the force of gravity acting on an object goes like this…

Material properties, introduction to forces and motion, plants and animals, and basic principles of earth science.

States of matter, weather, sound energy, light waves, and experimenting with the scientific method.

Chemical reactions, polymers, rocks and minerals, genetic traits, plant and animal life cycles, and Earth's resources.

Newton's law of motion, celestial objects, telescopes, measure the climate of the Earth and discover the microscopic world of life.

Electricity and magnetism, circuits and robotics, rocks and minerals, and the many different forms of energy.

Chemical elements and molecules, animal and plant biological functions, heat transfer, weather, planetary and solar astronomy.

Heat transfer, convetion currents, ecosystems, meteorology, simple machines, and alternative energy.

Cells, genetics, DNA, kinetic and potential, thermal energy, light and lasers, and biological structures.

Acceleration, forces projectile motion chemical reactions, deep space astronomy, and the periodic table.

Alternative energy, astrophysics, robotics, chemistry, electronics, physics and more. For high school & advanced 5-8th students.

Tips and tricks to getting the science education results you want most for your students.

Hovercraft, Light Speed, Fruit Batteries, Crystal Radios, R.O.V Underwater Robots and more!

There are three main differences between assuming the earth is round, uniformly dense, and not rotating as we did before.

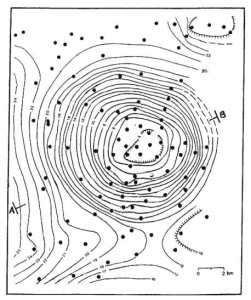

First, the crust is not uniform. There are lumps and clumps everywhere that vary the density add up to make small variations in the force of gravity that we can actually measure with objects in free-fall motion. It’s actually how scientists find pockets of oil in the earth. They measure the surface gravity and plot it out, and if there’s a large enough deviation, it means there’s something interesting underground.

First, the crust is not uniform. There are lumps and clumps everywhere that vary the density add up to make small variations in the force of gravity that we can actually measure with objects in free-fall motion. It’s actually how scientists find pockets of oil in the earth. They measure the surface gravity and plot it out, and if there’s a large enough deviation, it means there’s something interesting underground.

This image of the Mors salt dome in Denmark was studied for radioactive waste disposal. It’s a surface gravity survey that measures the acceleration due to gravity that shows something interesting is underground! The dots are the places where gravity was actually measured. You can read more about how gravity is measured from advanced lecture notes here. The unit of measurement for these deviations is called the “milligal” for Galileo, where 1 gal = 1,000 mgal = 1 cm/s3.

[/am4show]

The second problem with our assumption sis that the earth is not a sphere. It’s flattened a bit at the poles and bulges out at the equator. The ring around equator is larger than a ring around the poles by 21 km, which makes the poles closer to the center of the earth than the equator! Free-fall at the poles is slightly more than free-fall at the equator.

But before you book a trip to skydive in Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, Sao Tome, Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Kenya, Somalia, Maldives, Indonesia or Kiribati, let’s talk about the assumption we made… The earth really does rotate. That’s not a surprise. How does this affect the value of g then? The bottom line is that gravity changes with altitude from 9.78 to 9.84 m/s2., mostly due to the earth spinning, but some to the earth not being a perfect sphere.

Circular motion is a little different from straight-line motion in a few different ways. Objects that move in circles are roller coasters in a loop, satellites in orbit, DVDs spinning in a player, kids on a merry go round, solar systems rotating in the galaxy, making a left turn in your car, water through a coiled hose, and so much more.

For any object that goes in a circle (or you can approximate it to a circle), you’ll want to use this approach when solving problems. You can feel the effect of circular motion if you’ve ever been in a car that suddenly turns right or left. You feel a push to the opposite side, right? If you are going fast enough and you take the turn hard enough, you can actually get slammed against the door. So my question to you is: who pushed you? Let’s find out!

An object that moves in a circle with constant speed (like driving your car in a big circle at 30 mph) is called uniform circular motion. Although the speed is constant (30 mph), the velocity, which is a vector and made up of speed and direction, is not constant. The velocity vector has the same speed (magnitude), but the direction keeps changing as your car moves around the circle. The direction is an arrow that’s tangent to the circle as long as the car is moving on a circular path. This means that the tangent arrow is constantly changing and pointing in a new direction.

Now this next experiment is a little dangerous (we’re going to be spinning flames in a circle), so I found a video by MIT that has a row of five candles sitting on a rotating platform (like a “lazy susan”) so you can see how it works.

The candles are placed inside a dome (or a glass jar) so that when we spin them, they aren’t affected by the moving air but purely by acceleration. So for this video above, a row of candles are inside a clear dome on a rotating platform. When the platform rotates, air inside the dome gets swung to the outer part of the dome, creating higher density air at the outer rim, and lower density air in the middle. The candle flames point inwards towards the middle because the hot gas in the flames always points towards lower density air. Source: http://video.mit.edu

Now you’re beginning to understand how an object moving in a circle experiences acceleration, even if the speed is constant.

So what direction is the acceleration vector?

It’s pointed straight toward the center of that circle.

Velocity is always tangent to the circle in the direction of the motion, and acceleration is always directed radially inward. Because of these two things, the acceleration that arises from traveling in a circle is called centripetal acceleration (a word created by Sir Isaac Newton). There’s no direct relationship between the acceleration and velocity vectors for a moving particle.

Do you remember when I asked you “Who pushed you?” when you were riding in a car that took a sharp turn? Well, the answer has to do with centripetal force. Centripetal (translation = “center-seeking” ) is the force needed to keep an object following a curved path.

Remember how objects will travel in a straight line unless they bump into something or have another force acting on it like gravity, friction, or drag force? Imagine a car moving in a straight line at a constant speed. You’re inside the car, no seat belt, and the seat is slick enough for you to slide across easily. Now the car turns and drives again at constant speed but now on a circular path. When viewed from above the car, we see the car following a circle, and we see you wanting to keep moving in a straight line, but the car wall (door), moves into your path and exerts a force on you to keep you moving in a circle. The car door is pushing you into the circle.

According to Newton’s second law of motion, if you are experiencing an acceleration you must also be experiencing a net force (F=ma). The direction of the net force is in the same direction as the acceleration, so for the example with you inside the car, there’s an inward force acting on you (from the car door) keeping you moving in a circle.

If you have a bucket of water and you’re swinging it around your head, in order to keep a bucket of water swinging in a circle, the centripetal force can be felt in the tension experienced by the handle. Swinging an object around on a string will cause the rope to undergo tension (centripetal force), and if your rope isn’t strong enough, it will snap and break, sending the mass flying off in a tangential straight line until gravity and drag force pull the object to a stop.

This force is proportional to the square of the speed, meaning that the faster you swing the object, the higher the magnitude of the force will be.

Remember Newton’s First Law? The law of inertia? It states that objects in motion tend to stay in motion with the same speed and direction unless acted upon by an unbalanced/external force. Which means that objects naturally want to continue going their straight and merry way (like you did in a straight line when you were inside the car) until an unbalanced force causes it to turn speed up or stop. Can you see how an unbalanced force is required for objects to move in a circle? There has to be a force pushing on the object, keeping in on a circular path because otherwise, it’ll go off in a straight line!

Every object moving in a circle will experience a force pushing or pulling it toward the center of the circle. Whether it’s a car making a turn and the friction force from the road are acting on the wheels of the car, or a bucket is swung around your head and the tension of the rope keeps it moving in a circle, they all have to have a force keeping them moving in that circle, and that force is called centripetal force. Without it, objects could never change their direction. Because centripetal force is tangent to the velocity vector, the force can change the direction of an object without changing the magnitude.

Centrifugal (translation = “center-fleeing”) force has two different definitions, which causes even more confusion. The inertial centrifugal force is the most widely referred to, and is purely mathematical, having to do with calculating kinetic forces using reference frames, and is used with Newton’s laws of motion. It’s often referred to as the ‘fictitious force’.

Centrifugal (translation = “center-fleeing”) force has two different definitions, which causes even more confusion. The inertial centrifugal force is the most widely referred to, and is purely mathematical, having to do with calculating kinetic forces using reference frames, and is used with Newton’s laws of motion. It’s often referred to as the ‘fictitious force’.

You’ve come so far with your analysis that I really want to give you the “real way” to solve these types of problems. Normally, this method isn’t introduced to you until your second year in college, and that’s only if you’re an engineer taking Statics and Dynamics classes (the next level after this course).

Here’s a step-by-step method that really puts all the pieces we’ve been working on all together into one:

We’re going to build monster roller coasters in your house using just a couple of simple materials. You might have heard how energy cannot be created or destroyed, but it can be transferred or transformed (if you haven’t that’s okay – you’ll pick it up while doing this activity).

Roller coasters are a prime example of energy transfer: You start at the top of a big hill at low speeds (high gravitational potential energy), then race down a slope at break-neck speed (potential transforming into kinetic) until you bottom out and enter a loop (highest kinetic energy, lowest potential energy). At the top of the loop, your speed slows (increasing your potential energy), but then you speed up again and you zoom near the bottom exit of the loop (increasing your kinetic energy), and you’re off again!

Here’s what you need:

You can find circular motion everywhere, including football, car racing, ice skating, and baseball. An ice skater spins on ice, or a competition speed skater makes a turn… they are both examples of circular motion. A turn happens when there’s a force component directed inward from the circular path. Let me show you a couple of examples:

We’ve already studied the different types of forces and learned how to draw free body diagrams. We’re going to use those concepts to put forces into two different categories: internal and external forces. Internal forces include forces due to gravity, magnetism, electricity, and springs. External forces include applied, normal, tension, friction, drag and air resistance forces.

This is a nit-picky experiment that focuses on the energy transfer of rolling cars. You’ll be placing objects and moving them about to gather information about the potential and kinetic energy.

We’ll also be taking data and recording the results as well as doing a few math calculations, so if math isn’t your thing, feel free to skip it.

Here’s what you need:

What’s an inclined plane? Jar lids, spiral staircases, light bulbs, and key rings. These are all examples of inclined planes that wind around themselves. Some inclined planes are used to lower and raise things (like a jack or ramp), but they can also used to hold objects together (like jar lids or light bulb threads).

Here’s a quick experiment you can do to show yourself how something straight, like a ramp, is really the same as a spiral staircase.

When you toss down a ball, gravity pulls on the ball as it falls (creating kinetic energy) until it smacks the pavement, converting it back to potential energy as it bounces up again. This cycles between kinetic and potential energy as long as the ball continues to bounce.

Note: Do the pendulum experiment first, and when you’re done with the heavy nut from that activity, just use it in this experiment.

You can easily create one of these mystery toys out of an old baking powder can, a heavy rock, two paper clips, and a rubber band (at least 3″ x 1/4″). It will keep small kids and cats busy for hours.

This is a very simple yet powerful demonstration that shows how potential energy and kinetic energy transfer from one to the other and back again, over and over. Once you wrap your head around this concept, you’ll be well on your way to designing world-class roller coasters.

For these experiments, find your materials:

This experiment is for Advanced Students.There are several different ways of throwing objects. This is the only potato cannon we’ve found that does NOT use explosives, so you can be assured your kid will still have their face attached at the end of the day. (We’ll do more when we get to chemistry, so don’t worry!)

These nifty devices give off a satisfying *POP!!* when they fire and your backyard will look like an invasion of aliens from the French Fry planet when you’re done. Have your kids use a set of goggles and do all your experimenting outside.

Here’s what you need:

Bobsleds use the low-friction surface of ice to coast downhill at ridiculous speeds. You start at the top of a high hill (with loads of potential energy) then slide down a icy hill til you transform all that potential energy into kinetic energy. It’s one of the most efficient ways of energy transformation on planet Earth. Ready to give it a try?

This is one of those quick-yet-highly-satisfying activities which utilizes ordinary materials and turns it into something highly unusual… for example, taking aluminum foil and marbles and making it into a racecar.

While you can make a tube out of gift wrap tubes, it’s much more fun to use clear plastic tubes (such as the ones that protect the long overhead fluorescent lights). Find the longest ones you can at your local hardware store. In a pinch, you can slit the gift wrap tubes in half lengthwise and tape either the lengths together for a longer run or side-by-side for multiple tracks for races. (Poke a skewer through the rolls horizontally to make a quick-release gate.)

Here’s what you need:

We’re going to build monster roller coasters in your house using just a couple of simple materials. You might have heard how energy cannot be created or destroyed, but it can be transferred or transformed (if you haven’t that’s okay – you’ll pick it up while doing this activity).

Roller coasters are a prime example of energy transfer: You start at the top of a big hill at low speeds (high gravitational potential energy), then race down a slope at break-neck speed (potential transforming into kinetic) until you bottom out and enter a loop (highest kinetic energy, lowest potential energy). At the top of the loop, your speed slows (increasing your potential energy), but then you speed up again and you zoom near the bottom exit of the loop (increasing your kinetic energy), and you’re off again!

Here’s what you need:

Nothing says summer time fun than a home-built go-kart that can race down the driveway with just as much thrill as two story roller coasters.

A go-karts (also called “go-cart”) can be gravity powered (without a motor) or include electric or gas powered motors. The gravity powered kind are also known as Soap Box Derby racers, and are the simplest kind to make since all you need is wheels, a frame, and a good hill (and a helmet!).

If you’ve ever thrown a ball down into the sand, you know it can bury itself below the surface. Here’s how you figure out the non-conservative forces into the equation of the sand exerting a force on the ball as it slows down and stops deep in the sand.

Have you learned how to drive yet, or are you excited to learn? Here’s a question on the driver’s test that is really kind of scary from a physics point of view, but it will make a lot of sense once you see how it works. And might even keep you from speeding, now that you understand what can happen if you lock up your brakes while going too fast.

How do you calculate the energies of particles going near the speed of light? It’s a little tricky, but you can do it if you have the right equation. Since the kinetic energy equation comes from Newton’s Laws of Motion, which don’t apply to particles moving near the speed of light, we have to add a correction factor from Einstein’s Theory of Relativity in order to compensate and make the equations accurate. Here’s the equation for particles going close to light speed:

Work is not that hard… it’s force that can be difficult. Imagine getting up a 10-step flight of stairs without a set of stairs. Your legs don’t have the strength or force for you to jump up… you’d have to climb up or find a ladder or a rope. The stairs allow you to, slowly but surely, lift yourself from the bottom to the top. Now imagine you are riding your bike and a friend of yours is running beside you.

Who’s got the tougher job? Your friend, right? You could go for many miles on your bike but your friend will tire out after only a few miles. The bike is easier (requires less force) to do as much work as the runner has to do. Now here’s an important point, you and your friend do about the same amount of work.

You also do the same amount of work when you go up the stairs versus climbing up the rope. The work is the same, but the force needed to make it happen is much different. Don’t worry if that doesn’t make sense now. As we move forward, it will become clearer. Before we start solving physics problems, we first have to accurately define a couple of terms we’re going to be using a lot that you might already have a different definition for.

Here are three concepts we’re going to be working with in this section:

Energy is the ability to do work. Work is done on an object when a force acts on it so the object moves somewhere. It can be a large or small displacement, but as long as it’s not in its original position when it’s done, work is said to be done on the object. An example of work is when an apple falls off the tree and hits the ground. The apple falls because the gravitational force is acting on it, and it went from the tree to the ground. If you carry a heavy box up a flight of stairs, you are doing work on the box.

An example of what is not work is if you push really hard against a brick wall. The wall didn’t go anywhere, so you didn’t do any work at all (even though your muscles may not agree!). Mathematically, work is a vector, and is defined as the force multiplied by the distance like this: W = F d

If there’s an angle between the force and displacement vectors, then you’ll need to also multiply by the cosine of the angle between the two vectors. This is an important concept: Notice that the force has to cause the displacement. If you’re carrying a heavy box across the room (no stairs) at a constant speed, then you are not doing work on the box.

We’ll cover power in a little bit, but first we need to have a unit of measurement for work. The units for work and energy are the same, but note that energy and work are not the same. (Remember, energy is the ability to do work.)

For energy, a couple of units are the Joule (J) and the calorie (cal or Cal). A Joule is the energy needed to lift one Newton one meter. A Newton is a unit of force. One Newton is about the amount of force it takes to lift 100 grams or 4 ounces or an apple.

It takes about 66 Newtons to lift a 15-pound bowling ball and it would take a 250-pound linebacker about 1000 Newtons to lift himself up the stairs! So, if you lifted an apple one meter (about 3 feet) into the air you would have exerted one Joule of energy to do it.

This experiment is for Advanced Students. We’re going to really get a good feel for energy and power as it shows up in real life. For this experiment, you need:

This might seem sort of silly but it’s a good way to get the feeling for what a Joule is and what work is.

Please login or register to read the rest of this content.

A peanut is not a nut, but actually a seed. In addition to containing protein, a peanut is rich in fats and carbohydrates. Fats and carbohydrates are the major sources of energy for plants and animals.

The energy contained in the peanut actually came from the sun. Green plants absorb solar energy and use it in photosynthesis. During photosynthesis, carbon dioxide and water are combined to make glucose. Glucose is a simple sugar that is a type of carbohydrate. Oxygen gas is also made during photosynthesis.

The glucose made during photosynthesis is used by plants to make other important chemical substances needed for living and growing. Some of the chemical substances made from glucose include fats, carbohydrates (such as various sugars, starch, and cellulose), and proteins.

Photosynthesis is the way in which green plants make their food, and ultimately, all the food available on earth. All animals and nongreen plants (such as fungi and bacteria) depend on the stored energy of green plants to live. Photosynthesis is the most important way animals obtain energy from the sun.

Oil squeezed from nuts and seeds is a potential source of fuel. In some parts of the world, oil squeezed from seeds-particularly sunflower seeds-is burned as a motor fuel in some farm equipment. In the United States, some people have modified diesel cars and trucks to run on vegetable oils.

Fuels from vegetable oils are particularly attractive because, unlike fossil fuels, these fuels are renewable. They come from plants that can be grown in a reasonable amount of time.

Please login or register to read the rest of this content.

This experiment is for advanced students. Did you know that eating a single peanut will power your brain for 30 minutes? The energy in a peanut also produces a large amount of energy when burned in a flame, which can be used to boil water and measure energy.

Peanuts are part of the bean family, and actually grows underground (not from trees like almonds or walnuts). In addition to your lunchtime sandwich, peanuts are also used in woman’s cosmetics, certain plastics, paint dyes, and also when making nitroglycerin.

What makes up a peanut? Inside you’ll find a lot of fats (most of them unsaturated) and antioxidants (as much as found in berries). And more than half of all the peanuts Americans eat are produced in Alabama. We’re going to learn how to release the energy inside a peanut and how to measure it.

We’re going to learn how to calculate the amount of work done by forces by looking at how the force acts on the object, and if it causes a displacement. Have you spotted the three things you need to know in order to calculate the work done?

The easiest way to do this is to show you by working a set of physics problems. So take out your notebook and a pencil, and do these problems right along with me. Here we go!

Work done by friction is never conserved, since it’s turned into heat or sound, and we can’t get that back. It’s a non-conservative force. Other forces like gravity and speed are said to be conservative, since we can transfer that energy to a different form for a useful purpose. When you pull back a swing and then let go, you’re using the energy created by the gravitational force on the swing and transforming it into the forward motion of the swing as it moves through its arc. Energy from friction forces cannot be recovered, so we say that it’s an external energy, or work done by an external force.

Please login or register to read the rest of this content.

All the different forms of energy (heat, electrical, nuclear, sound, and so forth) can be broken down into two main categories: potential and kinetic energy. Kinetic energy is the energy of motion. Kinetic energy is an expression of the fact that a moving object can do work on anything it hits; it describes the amount of work the object could do as a result of its motion. Whether something is zooming, racing, spinning, rotating, speeding, flying, or diving… if it’s moving, it has kinetic energy.

How much energy it has depends on two important things: how fast it’s going and how much it weighs. A bowling ball cruising at 100 mph has a lot more kinetic energy than a cotton ball moving at the same speed.

Imagine an arrow is shot from a bow and by the time it hits an apple it is traveling with 10 Joules of kinetic energy (kinetic energy is the energy of motion). What’s meant by kinetic energy is that when it hits something, it can do that much work on whatever is hit.

Imagine an arrow is shot from a bow and by the time it hits an apple it is traveling with 10 Joules of kinetic energy (kinetic energy is the energy of motion). What’s meant by kinetic energy is that when it hits something, it can do that much work on whatever is hit.

Think of potential energy as the “could” energy. The battery “could” power the flashlight. The light “could” turn on. I “could” make a sound. That ball “could” fall off the wall. That candy bar “could” give me energy. Potential energy is the energy that something has that can be released. Objects can store energy as a result of their position.

In this experiment, you’re looking for two different things: first you’ll be dropping objects and making craters in a bowl of flour to see how energy is transformed from potential to kinetic, but you’ll also note that no matter how carefully you do the experiment, you’ll never get the same exact impact location twice.

To get started, you’ll need to gather your materials for this experiment. Here’s what you need:

What if you’re wanting to get a motor for a winch on the front of your jeep? What size motor do you need? Here’s how to calculate the minimum power so you don’t spend more cash than you need to for a motor that will still do the job. (Near the end of the video below, I’ll show you how to convert watts to horsepower.)